Introduction

What if society itself was the killer? What if the very systems designed to sustain us became complicit in acts of silent violence, leaving countless victims in their wake? This isn’t the plot of a dystopian novel; it’s the grim reality of what Friedrich Engels termed social murder.

Coined in the 19th century, Engels used the phrase to describe the avoidable deaths caused by systemic neglect and exploitation in industrial England. He argued that the working class suffered premature deaths due to the deliberate choices of those in power—choices rooted in greed and indifference. But social murder is far from an antiquated concept; it’s alive and thriving in modern society.

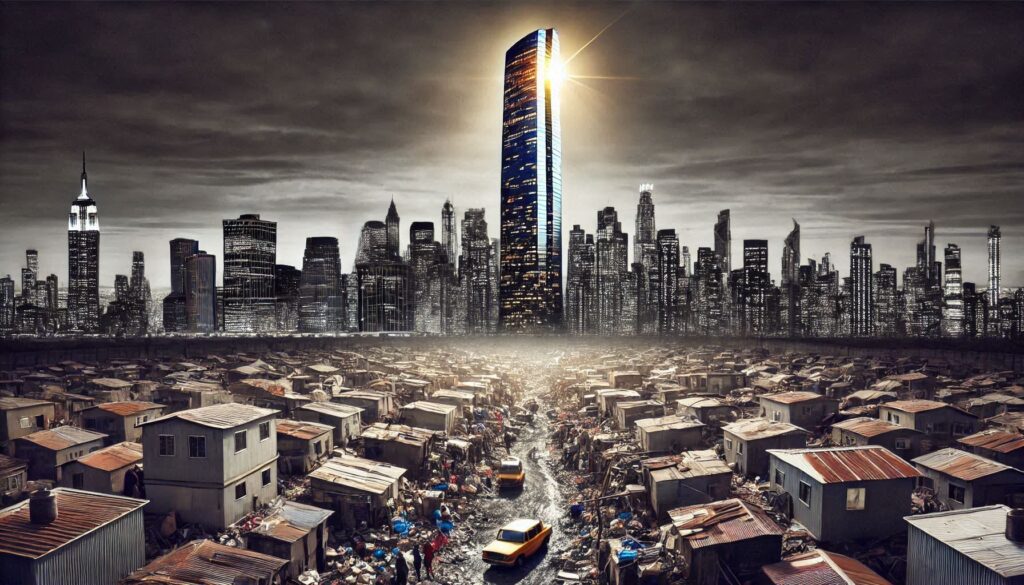

Today, we see its echoes in the disproportionate impacts of climate change on vulnerable communities, the staggering inequalities in access to healthcare, and the perpetuation of poverty that traps generations in cycles of despair. By exploring the origins, manifestations, and implications of social murder, we uncover a chilling truth: this phenomenon, born of systemic neglect and exploitation, remains one of the most pressing moral challenges of our time.

What is Social Murder?

Social murder, a term coined by Friedrich Engels in the mid-19th century, refers to the avoidable loss of human life caused by systemic neglect and exploitation. In his seminal work, The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845), Engels described how the appalling living and working conditions imposed on industrial workers in Victorian England led to premature death. He asserted that these deaths were not accidental but the direct result of deliberate choices made by those in power—choices prioritizing profit over people.

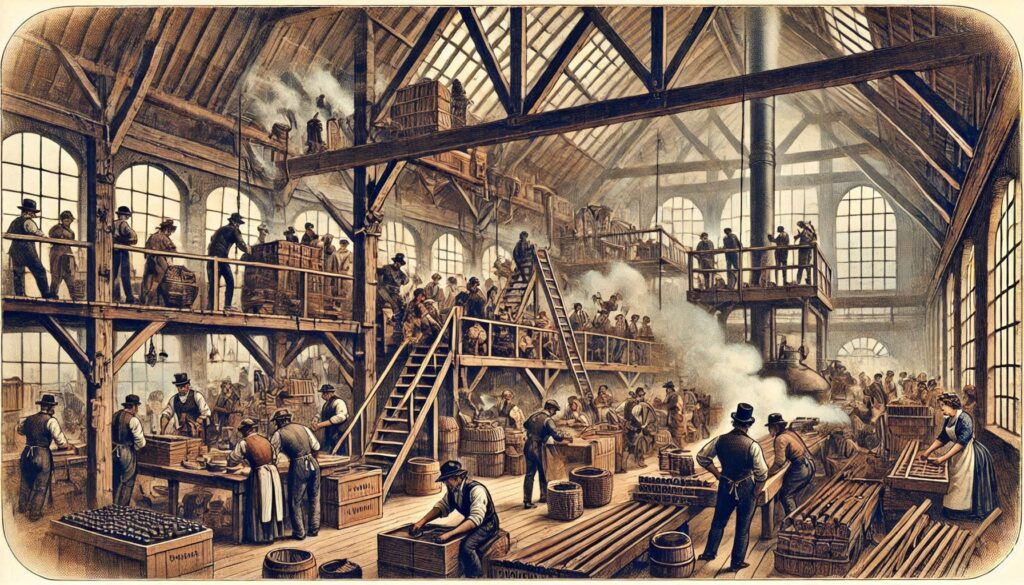

Engels’ observations were rooted in the grim realities of the industrial slums of Manchester, where overcrowded housing, poor sanitation, and unsafe workplaces were rampant. He documented how factory owners and policymakers, by failing to address these dire conditions, effectively condemned workers to lives of suffering and early graves. For Engels, this systemic harm amounted to murder—not through physical violence, but through neglect and exploitation so severe that death became an inevitable consequence.

Fast forward to today, and the concept of social murder is more relevant than ever. It has expanded beyond the industrial era to encompass a range of systemic harms caused by policies—or the lack thereof—that knowingly place vulnerable populations at risk. For example, inadequate healthcare access that leads to preventable deaths, environmental policies that exacerbate climate crises in marginalized communities, or economic structures that perpetuate poverty can all be seen as modern iterations of social murder.

By framing these issues as acts of systemic violence rather than mere misfortunes, the concept of social murder challenges us to confront the moral and ethical responsibilities of those in power. It underscores the collective culpability of societies that allow these injustices to persist.

Why Does Social Murder Happen?

Social murder is not an accident; it is the result of systemic and psychological factors deeply embedded in the fabric of society. By examining its causes, we uncover how deliberate policies, economic structures, and human psychology perpetuate this phenomenon, making it an enduring reality.

Systemic Causes

Economic Inequality and Exploitation

At the heart of social murder lies economic inequality. In systems where wealth and power are concentrated in the hands of a few, the lives of the marginalized are often devalued. Exploitation becomes the norm, with corporations and governments prioritizing profit over public welfare. Workers in low-paying jobs endure hazardous conditions and insufficient healthcare, all while generating wealth for the elite—a modern parallel to Engels’ Victorian observations.Structural Violence and Neglect

Structural violence refers to the harm caused by social structures or institutions that prevent people from meeting basic needs. When policies neglect education, healthcare, or housing for vulnerable populations, they create a breeding ground for poverty and premature death. This indirect violence often goes unnoticed, concealed by bureaucracy and systemic inertia.Profit-Driven Priorities

In a capitalist framework, profit often trumps human welfare. Whether it’s pharmaceutical companies pricing life-saving drugs out of reach, industries lobbying against environmental regulations, or governments cutting social programs to reduce costs, these decisions demonstrate a chilling indifference to human life.

Psychological Factors

Cognitive Dissonance and Normalization of Injustice

People often rationalize systemic injustices to reduce cognitive dissonance. Accepting that societal structures cause harm requires confronting uncomfortable truths about privilege, complicity, and responsibility—an emotional burden many avoid.Diffusion of Responsibility

In large systems, individual accountability often gets diluted. Policymakers, corporate executives, and ordinary citizens alike can feel that they lack the power to effect change, leading to collective inaction.Ingroup-Outgroup Bias and Cultural Narratives

Societal narratives often frame certain groups as “undeserving” of resources or protection. Racism, classism, and xenophobia perpetuate policies that disproportionately harm marginalized communities, normalizing their suffering.

The Role of Political Power and Lobbying

Political power dynamics play a pivotal role in perpetuating social murder. Powerful industries and lobbyists shape policies to serve their interests, often at the expense of public welfare. For example, fossil fuel companies have long funded misinformation campaigns to stall climate action, despite knowing the devastating consequences for vulnerable populations. Similarly, healthcare lobbying in many countries ensures that life-saving treatments remain a privilege rather than a right.

These power imbalances create a cycle where the wealthy and influential benefit from systemic injustices while the poor and marginalized bear the cost. The perpetuation of social murder is not just a result of passive neglect—it is actively reinforced by those who wield power and profit from the status quo.

Examples of Social Murder

Social murder manifests in diverse forms across time periods and contexts, from historical industrial exploitation to modern crises rooted in systemic neglect. Each example underscores how deliberate choices—or deliberate inaction—by those in power lead to devastating consequences for vulnerable populations.

Historical: Victorian England’s Industrial Exploitation

Friedrich Engels’ observations of 19th-century England provide the earliest documented examples of social murder. Industrial workers toiled in hazardous factories for long hours, earning meager wages while living in overcrowded slums with poor sanitation. Diseases like cholera and tuberculosis were rampant, and child labor was common. The ruling class, aware of these conditions, chose to maintain the exploitative system, prioritizing profit over the welfare of workers. These choices condemned countless individuals to premature death, setting the stage for the modern understanding of social murder.

Environmental: Climate Change and Environmental Racism

Environmental injustice is a modern iteration of social murder, where marginalized communities bear the brunt of ecological degradation. A stark example is Flint, Michigan, where residents were exposed to lead-contaminated water for years due to government negligence. Despite early warnings, officials delayed action, dismissing the concerns of the predominantly Black and low-income population. The result was widespread lead poisoning, long-term health consequences, and an erosion of public trust. Flint exemplifies how systemic failures and environmental racism create life-threatening conditions for the vulnerable.

Similarly, climate change disproportionately affects poorer nations and communities, which often lack the resources to mitigate its impact. Rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and resource scarcity hit these groups hardest, making them collateral damage in a global system that prioritizes profit over sustainability.

Healthcare: Lack of Universal Access in the U.S.

The United States offers another glaring example of social murder through its healthcare system. Millions of Americans lack access to affordable healthcare, leading to preventable deaths from treatable conditions. Diseases like diabetes and hypertension disproportionately affect low-income communities, where systemic barriers limit access to preventive care and medications. The absence of universal healthcare reflects a policy choice that values market-driven profit over human lives, exacerbating health inequities and perpetuating cycles of poverty and illness.

Labor Exploitation: The Rana Plaza Collapse

In 2013, the collapse of the Rana Plaza garment factory in Bangladesh highlighted the deadly consequences of labor exploitation. Over 1,100 workers, mostly women, died when the building, deemed structurally unsafe, was allowed to operate to meet the demands of global fashion brands. The incident exposed how multinational corporations prioritize profits over worker safety, perpetuating modern forms of industrial exploitation reminiscent of Engels’ Victorian England. Despite widespread outrage, exploitative labor practices remain rampant in developing nations.

Modern Crises: COVID-19 Pandemic Disparities

The COVID-19 pandemic starkly illustrated social murder on a global scale. Vulnerable populations, including low-income workers, racial minorities, and elderly individuals, suffered disproportionately from the virus due to systemic inequalities. In many countries, healthcare systems were overwhelmed, essential workers faced unsafe conditions, and governments prioritized economic recovery over public health. Vaccine distribution further highlighted disparities, with wealthy nations hoarding supplies while poorer nations struggled to vaccinate their populations. These inequities were not accidents—they were the result of deliberate policy choices that prioritized power and privilege over global solidarity.

Hunger in Affluent Nations: Food Deserts and Welfare Neglect

Even in wealthy nations, hunger persists as a form of social murder. Food deserts—areas with limited access to affordable, nutritious food—disproportionately affect low-income and minority communities. Coupled with the neglect of welfare programs, these systemic failures create a cycle where malnutrition and related health issues become inevitable. For example, in the U.S., cuts to food assistance programs leave millions reliant on food banks, perpetuating hunger in one of the richest nations in the world.

Deep Dive: The Flint, Michigan Water Crisis

The Flint water crisis remains one of the most chilling examples of social murder in recent history. In 2014, in a cost-cutting measure, officials switched Flint’s water source to the Flint River without implementing adequate corrosion controls. The water corroded old pipes, leaching lead into the water supply. Despite residents reporting foul-smelling, discolored water, government officials downplayed the risks for over a year.

The impact was catastrophic: tens of thousands of children were exposed to lead, which can cause irreversible brain damage and developmental delays. The crisis also led to outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease, claiming at least 12 lives. Flint’s predominantly Black and low-income population was dismissed and ignored, illustrating how systemic racism and negligence can result in devastating harm.

The Flint crisis wasn’t an isolated incident—it was the predictable outcome of a system that prioritizes cost savings over public health, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities. It serves as a grim reminder that social murder isn’t always loud or immediate; often, it is a slow, systemic process, hidden in the decisions of policymakers and institutions.

The Psychology Behind Social Murder

Understanding why social murder persists requires delving into the human psyche and societal dynamics. The normalization of systemic harm, societal biases, and cognitive dissonance all play a role in enabling the structures that perpetuate this phenomenon.

Normalization of Systemic Harm

When injustice becomes routine, it often fades into the background. Structural issues like poverty, inadequate healthcare, or environmental degradation are so deeply entrenched in society that they are often perceived as inevitable rather than correctable. This normalization dulls the moral outrage that would otherwise prompt collective action. Over time, systemic harm becomes accepted as part of the status quo, allowing those in power to evade accountability.

Societal Biases and Economic Hierarchies

Societal biases and ingrained hierarchies further dehumanize the victims of social murder. Economic and racial inequalities lead to the marginalization of certain groups, framing their suffering as less urgent or undeserving of attention. For example, narratives that blame poverty on personal failure instead of systemic issues shift responsibility onto individuals, deflecting criticism from the structures that perpetuate inequality. These biases create a psychological distance between the privileged and the oppressed, making it easier to ignore or justify systemic harm.

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance—the mental discomfort experienced when holding conflicting beliefs—also contributes to inaction. Confronting the reality of social murder means acknowledging complicity in a system that causes harm. To avoid this discomfort, individuals and institutions rationalize their behavior or deny the problem altogether. Phrases like “it’s just the way things are” or “change takes time” become psychological defenses, preventing meaningful action against systemic injustices.

Social murder endures not only because of deliberate policy choices but also because of the psychological mechanisms that allow society to turn a blind eye. Breaking this cycle requires addressing these underlying biases and challenging the normalization of harm, forcing both individuals and institutions to confront uncomfortable truths.

Hope for Change: Addressing Social Murder

While the concept of social murder paints a grim picture of systemic harm and neglect, hope lies in the possibility of change. History has shown that collective action, policy reform, and shifts in societal values can disrupt even the most entrenched injustices.

Advocating for Systemic Reform

Tackling social murder requires bold systemic changes. Governments must prioritize universal healthcare, enforce stricter labor protections, and implement sustainable climate policies. These reforms address the root causes of systemic harm, ensuring that economic priorities no longer overshadow public welfare. For example, expanding access to healthcare and addressing food deserts can drastically improve quality of life for marginalized communities. International collaboration on climate change can mitigate environmental disasters that disproportionately affect vulnerable populations.

Grassroots Movements and Policy Successes

Grassroots movements have proven to be powerful catalysts for change. The civil rights movement, environmental justice campaigns, and workers’ unions have all reshaped policies and societal norms in the past. Recent successes, such as increased corporate accountability for supply chain ethics and local renewable energy initiatives, demonstrate how collective advocacy can create tangible improvements. These movements remind us that change often starts at the community level before reverberating through larger systems.

Encouraging Accountability

Individual and collective accountability are key to addressing social murder. Recognizing the privilege and biases that perpetuate systemic harm is the first step. Supporting ethical businesses, voting for equitable policies, and engaging in community activism empower individuals to contribute to broader change.

By refusing to accept systemic harm as inevitable, society can work toward a future where equity, compassion, and justice guide decision-making. The eradication of social murder is not just a moral imperative but a testament to humanity’s capacity to evolve and build a fairer world.

Conclusion

Social murder is not merely a relic of the past; it is a pervasive and ongoing reality embedded in the systems that shape our world. From Engels’ observations of Victorian England to modern crises like climate change, healthcare inequities, and labor exploitation, the concept highlights the devastating consequences of systemic neglect and exploitation.

However, acknowledging the existence of social murder is the first step toward dismantling it. By advocating for systemic reforms, supporting grassroots movements, and holding institutions accountable, we can challenge the structures that perpetuate harm.

The fight against social murder requires both awareness and action. Let this be a call to question injustices often accepted as inevitable, amplify the voices of the marginalized, and work collectively toward a future where every life is valued and protected. Change begins with each of us, but its impact can reshape societies for generations to come.